Are blockchains databases?

At Vendia, we can’t help ourselves. We ponder things past, present, and future — always looking for patterns and opportunities to make things better, smarter, and more effective. In this post, we’ll walk through some of the thinking and questioning behind our technology with a focused look at blockchains and database technology and explore these three questions:

- What's the fundamental difference between database and blockchain technologies?

- Will they remain forever independent, driven by radically different requirements?

- Or, are they on a collision course, with the ultimate future expression of data storage being something that possesses elements of both? (Spoiler alert: Yes, they are on collision course.)

Let’s start with some basics that get at the heart of databases' and blockchains' function and value.

Blockchains versus databases

Modern cloud-based databases are about making data durable. Typically, they make data durable by storing replicas of data on different physical devices. Blockchains like Hyperledger Fabric are another way to replicate and store data, sometimes even including a conventional database as part of their architecture.

We think of blockchains and databases as cousins. Here are some ways in which databases and blockchains are similar:

- Assuming we include materialized world state in our definition of a blockchain, both technologies support reading and writing data values.

- Both blockchains and databases offer some flavor of "transactions" and ordering. With a little work, an application can arrange for one update to occur before or after another, and it can know when an update is complete.

- And after a fashion (squinting intentionally a little bit here), both are durable stores. Databases are designed to survive machine crashes without loss of data, and — if you have enough nodes in availability-decorrelated locations — a blockchain can survive even permanent removal or loss of any individual replica.

So, pretty similar, right?

Differences between blockchain and database capabilities and characteristics

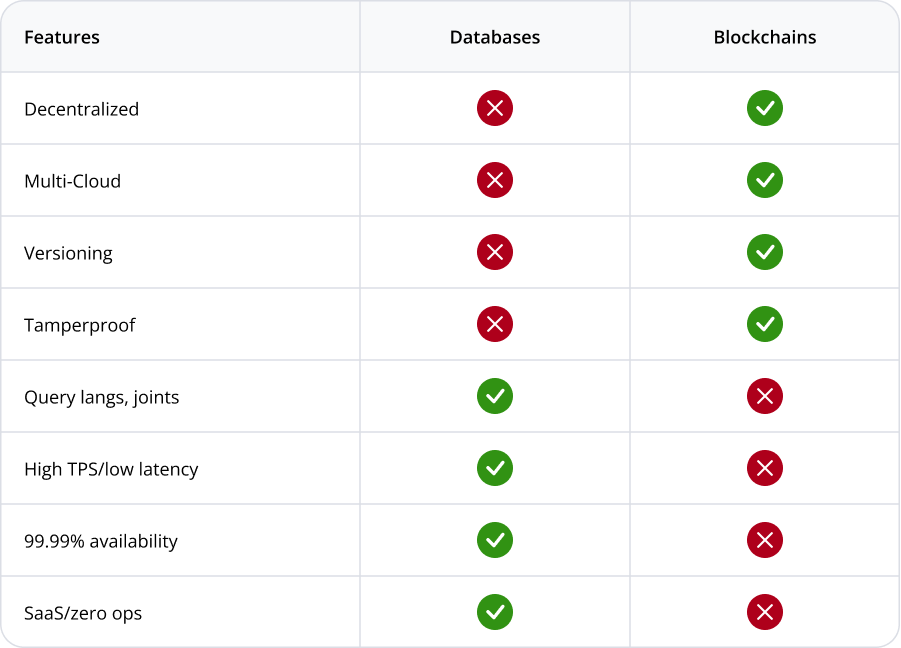

When we peer more closely, however, database and blockchain technologies start to feel different (Table 1).

Table 1: A high-level feature comparison of databases and first-generation blockchains | NOTE: Database companies outside of cloud service providers may offer multi-cloud capabilities, but none with the reach of a self-deployed blockchain.

Examples of blockchain capabilities and characteristics

For example, blockchains have some properties not normally found in run-of-the-mill databases.

- A ledger in the user-visible capabilities means that blockchains can support versioning (access to historical information) and lineage (you can determine when data was changed, and by whom).

- Blockchains also typically offer some flavor of immutability and "tamperproofing" — it's possible to know whether anything that was present before has gone missing or has been corrupted.

- Some databases offer automatic backups, but that's not quite the same thing as full history or integrity validation.

- Public blockchains also usually have a global notion of end user identity that's wired directly into the transaction model and semantics — something that's not a conventional feature of databases, possibly apart from some built-in logging support on the side.

Blockchains have another defining characteristic — decentralization

Conventional databases, even in their modern cloud-based incarnations, are designed to be owned, secured, and managed by a single entity. Keeping control of the data isolated to its owner is a defining characteristic of a modern cloud database where data security, isolation and governance are considered key design tenets.

Blockchains, by contrast, are decentralized ledgers — distributed not among machines in a cloud provider's data center for durability, but across multiple parties. These parties may be in a business relationship, but generally, these parties don't "trust" one another in the IT sense. Trust breaks down because, typically, each party has their own copy of the data, their own hardware and software systems, their own security teams and protocols, and so on.

Blockchains deliver a single source of truth, maintained automatically among all parties — regardless of where they reside.

Think about the last purchase you made with your credit card. For instance, maybe you bought a jacket on Nordstrom.com using your Visa card. Obviously, all of those vendor parties need to have independent IT systems. But they also need to share data to perform transactions, reconcile accounts, and contribute to a positive customer experience.

With decentralization comes a variety of capabilities we tend to associate with blockchains — data replication that can span companies, clouds, regions, accounts, and tech stacks while also ensuring the following conditions:

- Consistent

- Immutable

- Totally ordered

- Non-repudiable

In simpler words: blockchains deliver a single source of truth, maintained automatically among all parties — regardless of where they reside. …That's an incredibly powerful mechanism, one that doesn't normally show up in your typical database provider's list of features.

Examples of database capabilities and characteristics

Databases also have a set of abilities that most blockchains don't share. NOTE: To keep our comparisons somewhat equivalent, we'll limit our definition of "database" here to broadly adopted cloud-hosted SQL and NoSQL databases, such as Google Spanner, Azure CosmosDB, and AWS's Amazon Aurora and Amazon DynamoDB. These services have a number of characteristics that are fundamental to their usage in building scalable, enterprise-grade applications that can store and operate on real-time data in mission-critical business applications. Let’s take a look at a handful of the key characteristics.

No. 1 – Query languages (including joins and transactions)

One of the most obvious differences between databases and blockchains is that the data in a database can be atomically grouped and accessed in powerful ways, most commonly using SQL. Joins (or more broadly speaking, the ability of the database itself to search and group the data it holds) are a powerful feature not readily available on blockchains.

On blockchains, each individual item must be retrieved in isolation and then processed in application logic to perform the equivalent of a join, union, nested query, or any other non-trivial access pattern. Similarly, ACID (atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) transactions that allow users to atomically group updates together at the application level are not necessarily available in blockchains, but they are a given in modern cloud databases.

No.. 2 – Highly available

While a blockchain creates chain-level durable storage, if there are many regionally and cloud-segregated parties using it, each individual node is running on a single machine. Thus, it is not resilient to server failure. A single server crash causes a 100% outage for that node. By contrast, a table in a service like DynamoDB or CosmosDB is highly resilient to individual machine and even zonal outages. As a result, databases distinguish themselves from blockchains by offering 99.99% or better availability with no effort or deployment complexity on the part of their owner.

No. 3 – High throughput and low latency

Public chains like Ethereum that rely on proof of work can take many minutes to reach finality (the point at which data is effectively immutable for all time forward with no chance of being changed). Even private, permissioned blockchains such as Hyperledger Fabric can take several seconds to reach finality.

- Ethereum's throughput is around 15 transactions per second (TPS) for all users in aggregate.

- Hyperledger Fabric's throughput depends on its deployment details, but it's difficult to achieve better than a few hundred TPS of sustained performance without errors.

- By contrast, Amazon's DynamoDB can achieve 89 million TPS with single digit millisecond latency, and that's just for one of their millions of customers. Total aggregate capacity, while not published by AWS, is undoubtedly much higher.

No. 4 – Low per-transaction cost

Thanks to highly multi-tenanted cloud-based implementations, databases like the ones we're discussing here are extremely cost effective on a per transaction basis. During the month of January 2022, the lowest daily average Ethereum single transaction cost was $25.83 (the highest was approximately twice that amount). Meanwhile, an on-demand database write to Amazon's DynamoDB in the us-east-1 region costs $0.00000125, making Ethereum a minimum of 20,664,000 times more expensive than a conventional database.

No. 5 SaaS | Zero ops | Built-in scaling

Deploying a blockchain at production-scale at a company like Coinbase, that requires production-grade blockchain infrastructure, requires a large, knowledgeable team, non-trivial infrastructure spend to manually manage blockchain storage and create localized redundancy with backups, and complex, ongoing monitoring of both the infrastructure and the blockchain software that runs on it.

By contrast, a database like Google Spanner or Azure CosmosDB is hands-off. The developer never sees the underlying servers, operating systems, database software deployments, machine-level scaling operations, etc. Therefore, the underlying storage automatically expands, no matter how large a database table becomes. For a company without senior engineers to spare (or the big bucks to pay them), that's a huge difference in cost of ownership — especially when coupled to the lower per-transaction costs of databases versus blockchains, and the need to scale blockchain deployments to peak capacity 24x7x365.

Blockchain and database trends

Clearly blockchains and databases have emerged from sufficiently different origins and look fairly different at the moment in both use case requirements and implementation technology. But are these differences destined to remain?

Let's look at some interesting trend lines that might predict future states.

How databases and blockchains are becoming more alike

Blockchains are starting to take on some of the trappings of databases:

- Companies like Infura and Alchemy now offer "Blockchain as a Service.” This is a play to create higher availability, fully managed (serverles) solutions that are more like traditional cloud services and less like individually self-deployed, error-prone blockchain nodes. …Of course, purists might complain that having a centralized agency providing blockchain capability defeats some of its decentralized nature.

- Protocols like IPFS are attempting to expand on the narrow range of datatypes supported by blockchains, including operating as a file system for the web that can also treat large, unstructured. or semistructured data as being "on-chain."

- Researchers, practitioners, and businesses are looking at ways to simulate lower transaction costs through batching and other so-called Layer 2 (L2) solutions. As a concrete example, Coinbase addresses the throughput limitations and high per-transaction cost of blockchains like Ethereum by batching purchases from many users together into a single composite transaction.

- Many approaches exist to convert well-known blockchain ledger formats like Ethereum into more traditional databases. This effectively enables query languages such as SQL to be used on them, even though the fundamental Ethereum protocol doesn't directly support such functionality.

- At Vendia, we’re combining classic database capabilities, such as dirty read avoidance and ACID transactions, with blockchain and distributed ledger technologies.

On the blockchain side, the reasons for the convergence are obvious: database feature sets and the operational and cost expectations of businesses for these use cases have emerged over many decades for good reason, and those reasons aren't going away. Commercial blockchain solutions will have to meet those business expectations or die trying.

What customer doesn't want to be able to time travel through older versions of data, sleep better knowing their data is tamperproof, or eliminate the overhead of application logs by integrating lineage directly into the data model itself?

The pressure on databases to adopt blockchain capabilities are a little more subtle. A bit of this is healthy competition. For instance, while not yet embracing multi-party decentralization, cloud databases are gaining some capabilities that take them a step closer to blockchain-style capabilities:

- Google Spanner enables a single owner (account) to have a table that spans multiple geographic regions; each region can make updates seen by all the others.

- Snowflake allows a table owner on one cloud to share that table with a reader from another company on a different cloud.

- Amazon QLDB and Oracle Blockchain Tables support ledgering, an immutable and ordered log of updates that can help establish the lineage of a change and provide for versioned queries that can retrieve data as it existed in the past, not just in the present.

And what customer doesn't want to be able to time travel through older versions of data, sleep better knowing their data is tamperproof, or eliminate the overhead of application logs by integrating lineage directly into the data model itself? But beyond that, database users are also operating in increasingly regulated environments. Here are some examples:

- GDPR and CCPA/Prop 24 have made it necessary to control personal identifiable information (PII) not just within a company, but across companies.

- Financial and other regulations require tracking anything that involves money or credit more carefully than ever before, including being able to audit what was changed, when, and by whom.

- With increased focus on fairness and transparency, it’s unlikely that government agencies will be happy with data storage solutions that readily "forget" old copies of data or that can't be shared easily with auditors, other agencies, or consumers.

In this environment (which affects businesses of all sizes, shapes and sectors) blockchains and their feature set no longer feel novel or unique. Instead, it starts to read like the "must have" requirements of a typical enterprise application.

The future of databases and blockchains

At Vendia, we believe that the future isn't about databases versus blockchains. Rather, we believe they will exist as a single, unified data abstraction. The reasons are simple:

- All companies need to share data, both internally and externally.

- No one company or department within an organization can force all the data producers and consumers to agree on a single, centralized IT stack.

- Applications that work with that data need all their conventional expectations for databases to be met: from highly available uptime with a stringent SLA, to fully managed ("serverless") support, to high speed and low cost transactions.

Vendia Share was created with the belief that these two technologies aren't mutually exclusive, but complementary — so much so that combining them offers the best enterprise data management experience for the next generation of applications and the organizations that will win with them.

Learn more about blockchains and their integration with database capabilities for IT use cases. Or contact us directly to dive deeper with insights specifically for your organization and use cases.