APIs don’t have to be so difficult

Overcome the limitations of APIs and build a better future

APIs are the central building blocks of services, especially modern, cloud-based designs. They encapsulate complexity, can provide both operational and implementation isolation among different teams , and serve as the literal embodiment of domain driven designs. Proficiency in developing, deploying, and consuming APIs is one of the hallmarks of a healthy, effective IT organization; for many modern SaaS and financial service companies, such as Twilio and Stripe, APIs literally are the business.

Building great APIs should be simple: All major cloud providers offer highly scalable, fully managed services that remove virtually all infrastructure challenges from both API owners and consumers. Google Apigee, Amazon API Gateway, and Azure API Management handle the challenges of hosting, deploying, scaling, and making API infrastructure fault tolerant. They also provide built-in monitoring, logging, and a variety of authentication and management features. In addition, a well-known standard (OpenAPI, formerly known as “Swagger”) and a host of free tools make it easy for any developer to generate APIs from declarative descriptions.

But despite this robust toolbox, building systems that share data across organizations or business partners using APIs remains one of the most challenging and expensive propositions an IT team faces, impacted by scalability and fault tolerance requirements, burdened by security and compliance concerns, and frequently guilty of cost and development time overruns. Why this seeming impedance mismatch between a well-understood, well-supported development activity and the often expensive, unpredictable, and problematic result?

The answer is actually quite simple: It’s not the API that’s the problem, it’s the data the API carries.

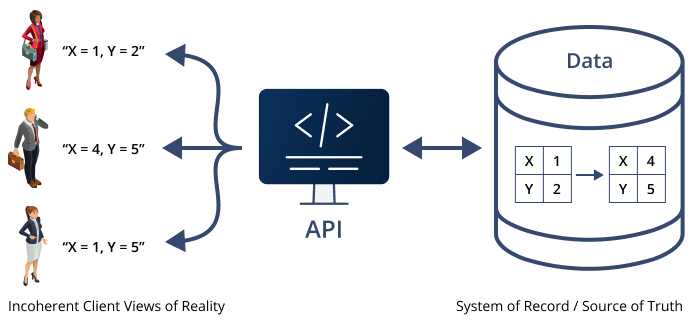

The moment that an API producer returns data to an API consumer, that data immediately becomes a stale copy of the data maintained by the API producer. In other words, versions of the truth (the one in the API producer and the one in the API consumer) start to immediately drift apart. Worse, there are often many consumer of an API, calling it at different times to retrieve the (ostensibly) same data, leading to many competing snapshots and variations on “the truth” of the data. Figure 1 illustrates this “chaos by design” pattern.

Figure 1: APIs create a partial, out of date, and incoherent view of the truth by handing out snapshots of the data at different times for different clients, without regard to cross-client consistency or correctness.

Why does this matter so much? Because most APIs exist precisely to share data.

While APIs can be used for other purposes, such as to control an IoT device, the bulk of APIs calls made by companies are for the purpose of sharing data between two or more systems. Outside of rare circumstances, such as when the data being shared will never change, that means that clients can never be sure they have the “real” version. And since that data is often critical to the functioning of a business – financial transactions for a bank, tickets for an airline, supply chain status for a manufacturer – having that data be inconsistent, incomplete, or out of date between the various parties results in serious business problems.

It’s a data consistency problem

To understand why problems with APIs are fundamentally problems with data, let’s expand the field of view to include a little more of the systems that surround the API proper.

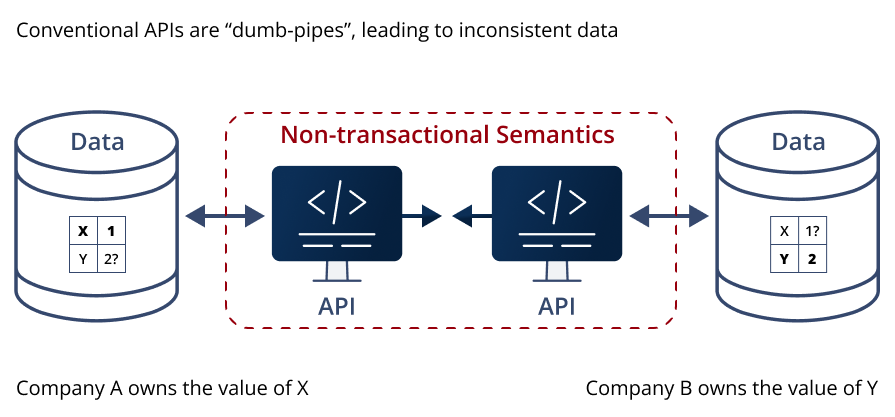

Figure 2: Conventional APIs are “dumb pipes”; they lose the integrity of the systems of record they’re supposed to represent, leading to incoherent copies and uncertainty for their business owners.

Figure 2 zooms out from the API per se to look at what is really happening in the broader context of sharing operational data between two systems.

The API producer can be related to its consumers in various ways:

- Two services within the same application

- Two applications within the same company, on the same cloud

- Two applications within the same company but owned by different organizations and running on different clouds

- Two applications owned by two different companies

… and so on. What’s important here isn’t the specific relationship between the API producer and each of the consumers. Rather, that for some reason – legal, geographic, contractual, security, compliance, architectural, or other – the data they operate on is related but segregated, which requires an API between them.

That duality is key:

- If the two systems didn’t require operational, security, legal, or other separation, they could simply be combined into one. The API is responsible for “firewalling” the two systems for one or more key, and presumably unchangeable, reasons.

- If the two systems did not need to share at least some of their data, there would be no need for the consumer to ever call the API. Thus, by construction some subset of the data held in the producer’s data storage system needs to be replicated (though not necessarily in its entirety or in its original format) into the consumer’s data storage system.

Once we reorient to view an API as a data sharing problem, rather than a “moving bits around” problem, the problem with this architecture is obvious: The API per se is a dumb pipe; it knows nothing about the data it carries.

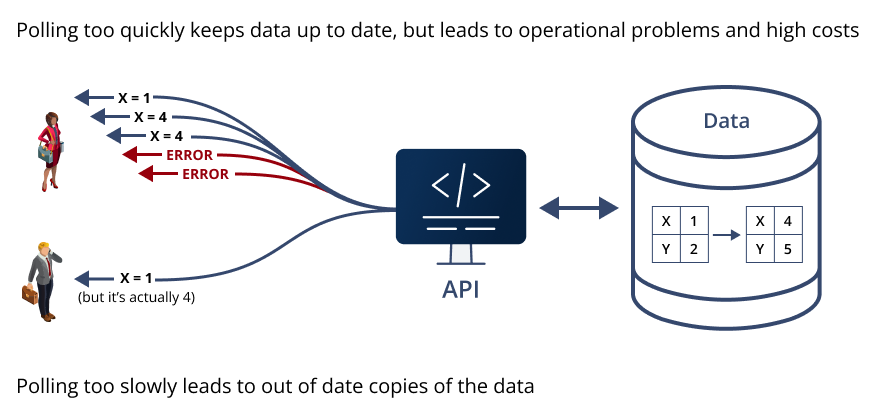

And since the producer continues to generate new data (and typically also alters or deletes existing data), the consumer has an impossible problem: If it polls (calls the API) too frequently, it will exhaust capacity on both sides with wasted work, but if it calls too seldom, the consumer will be working with out of date information.

There’s no way to win the “polling game”.

Figure 3: The “Polling Conundrum” – Polling too quickly hits operational limits and can lock clients out or even crash the infrastructure on which it runs. Polling too slowly allows information to drift even further out of date (and makes clients even less consistent with one another).

Alternative architectures

The realization that data-centric APIs are an attempt to create a “distributed database without the actual database” is hardly new. Almost a century ago, computer scientists realized that keeping multiple copies of any kind of data consistent required transactions, and early versions of databases were born.

With all the sophisticated progress in database technology since, why can’t we “just do that” to make the problem go away? Let’s take a look at some of the options that exist.

Multi-region databases

Some subsets of data-centric sharing relationships have easy, effective solutions to the inherent inconsistencies of APIs. The most obvious example are cloud databases that can replicate their data without the need for application-level involvement. \

This approach is simple (usually requiring nothing more than a configuration setting), but only applies when the producer and consumer of the data share the same company, don’t need account isolation, don’t need to cross public clouds, etc. Often there is also a loss of semantic integrity as well when moving from single to multiple regions – for example, Amazon DynamoDB reduces the semantics of cross-region data from “strongly consistent” to “eventually consistent”, and SQL databases often induce replication delays in multi-region replicas.

Event-based architectures

In an attempt to solve the “polling conundrum”, cloud providers have started offering event-based architectures as an alternative. The underlying problem with polling is that the consumer isn’t in a position to know when the data inside the producer has changed, so it inevitably ends up over- or under-polling as a result. In other words, the consumer is trying to do two things at once:

- Figure out when the data changes

- Actually receive the changed data when it does

It’s the first of these two that’s problematic: The consumer will never be in a good position to figure this out efficiently from the “outside looking in”.

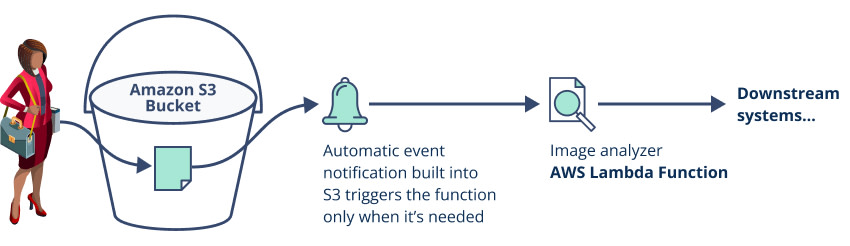

Event-based systems address this problem by flipping the relationship around: The producer notifies (calls) the consumer when there’s work to be done. The consumer, meanwhile, sits there quietly until it’s told there’s work for it to do (see Figure 4). Event-based systems are sometimes referred to colloquially by underlying technology choices (“webhooks”) or other nicknames (“callbacks”, “notifications”, “events”).

Event architectures can be built into existing cloud services (such as Amazon’s S3 bucket event delivery, shown in Figure 4). They can also be created in an “ad hoc” fashion through the use of generic event handling services such as Amazon EventBridge or Azure Event Hubs.

Figure 4: A basic event-based architecture. Files are uploaded to an Amazon S3 bucket, which has been configured to automatically send creation events to an image analyzer in the form of an AWS Lambda function. The “data API” between the bucket and the function is handled automatically by AWS, with no code or management required by the application owner.

Event-based architectures can be a powerful alternative to API-based polling approaches. However, they require every system involved, including the data producer and all its potential consumers, to participate in the design in order for it to work effectively. Built-in event handling systems are also usually confined to a single cloud provider, such as the Amazon S3 bucket events triggering AWS Lambda functions illustrated in Figure 4.

The moment crossing clouds, accounts, or companies is required, this particular pattern falls apart.

Other issues that can impact event-based architectures:

- Getting all parties involved to agree on the event format (schema), especially if that schema is dictated by the public cloud service provider, as is the case with Figure 4’s example

- Guaranteeing delivery – handling errors, retries, and “back pressure detection” if the consumer isn’t able to receive updates at the event the producer is delivering them, including the ability to replay events

- Whether ordering is preserved by all the event handlers involved in the process

- Securing cross-party event delivery

- Long-term storage of events, particularly if business relationships require new parties to be brought on board and “caught up” on historical events (since most event-based systems can only “hold onto” an event while it’s being delivered)

These problems can often be overcome within the confines of a single cloud, single organization, and single application, making event-based designs a compelling alternative to APIs within an organization. However, when large amounts of data needs to cross cloud or company boundaries, or when the parties involved have differing IT architectures, event-based architectures become increasingly difficult to achieve. Unfortunately, only a very tiny percentage of IT systems today enable ordered, consistent, guaranteed delivery of events between organizations or across different clouds, causing companies to fall back to APIs, with all their inherent data consistency issues in most cases.

Real-time streaming architectures

One particularly important subset of event-based systems are the real-time streaming architectures, such as the various flavors of Kafka and cloud services such as Amazon’s Kinesis.[^1] Event-based architectures are often “bolt-ons” – for example, the event system shown in Figure 4 was added to S3 when AWS introduced Lambda, many years after S3 had been in market. As a result, it lacks sophisticated data capabilities – not just streaming APIs per se, but batching, ability to “time travel” over buffered data, support for multiple clients reading from the same stream, etc.

Real-time streaming architectures solve these problems: rather than focus on an individual, isolated event payload, they treat data as an infinite stream, plumbed from one or more sources to one or more sinks. They address many of the limitations of more primitive event-handling systems, such as guaranteed in-order delivery, multiple consumers (each of whom may consume at a different rate and from a different point in the stream), sophisticated data batching and limited time travel capabilities, and more.

Most importantly, real-time streaming architectures avoid operational impedance mismatches. One of the chief limitations of primitive event-driven systems is that they force all consumers to consume at the same rate that the producer creates or changes data, which defeats the operational isolation that is one of the chief benefits of APIs.

Stream-based solutions restore this capability by including a stateful, built-in “queue”, unlike the more ephemeral solution of event-based notification approaches. The producer and each of the (possibly many) consumers can all be operating at different speeds (up to the limits of the producer’s buffering capacity, at least). Real-time streaming solutions also include sufficient metadata for clients to ask and answer questions such as, “am I falling behind the producer’s average rate of event emission?”

One of the things streaming solutions often lose relative to event-based delivery is a rigorous domain model: Because streaming infrastructure is complicated, even when delivered as a managed cloud service, it typically comes in a “one size fits all” approach. The payloads are just that: Uninterpreted bits. It’s up to the producer and the consumer to layer a detailed data model on top, turning the “stream of bits” into a “stream of business objects”, such as orders, shipments, invoices, etc.

Another problem with streaming solutions is their high cost: Buffering data requires storage, guaranteed delivery requires compute, and all of that doesn’t come for free. Unlike APIs and simpler event-driven systems where the data is only held while in transit (i.e., “on the wire”), streaming solutions have to provide durable storage for days or weeks of time.

Ironically, that’s also where they’re weak: Streams and events share a “fatal flaw” when trying to connect what are, at the end of the day, two or more data persistent systems: They’re not databases. Once the data has been sent by an event-based system or consumed by all the readers in a stream-based system,[^2] it’s gone forever.

Real-time streaming solutions share the same problems as centralized databases: They work when the producer(s) and consumer(s) are all owned and operated by the same entity, run on the same cloud, and live in the same (or at least closely related) accounts. Once it becomes necessary to break those limiting assumptions, they stop being viable solutions.

Legacy blockchains

Blockchains were supposed to be the answer to the problem of building modern data sharing architectures: A consistent and immutable ledger transparently, securely, and unimpeachably recreated in multiple, separately owned databases operated by legally unrelated (and mutually distrusting) parties. So, what happened?

First, blockchains never managed to address the fundamental scaling and throughput challenges. Public chains like Ethereum max out at 14 transactions per second in worldwide aggregate capacity, and even “private” chains can struggle to maintain 100 tps. These limitations make them ill suited to replace operational data stores that typically process thousands, tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of transactions per second.

Cost and complexity are also considerations: From the need to learn novel programming languages to their “deploy at peak capacity” design, legacy blockchains are expensive to develop, deploy, operate, and scale. They also aren’t particularly easy to use: Because they lack a data model (or even the capacity to model data) they tend to make poor databases, leaving all that complexity to the applications, and necessitating a complex “meta chain” on top of the primary chain to share a coordinated data model among partners. Taken together, these development, deployment, and coordination challenges often cause blockchain projects to fizzle, even in otherwise successful IT organizations.

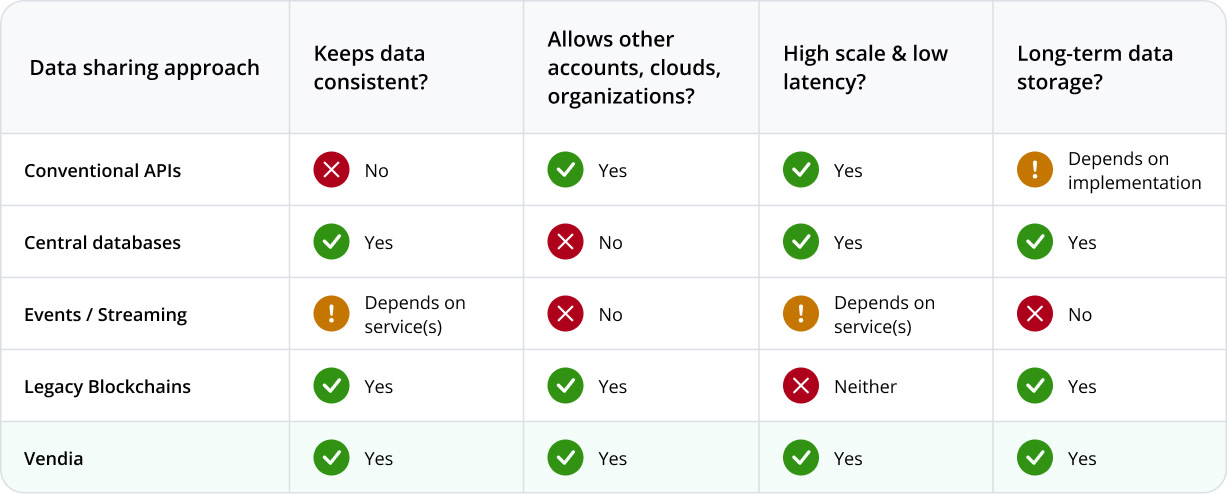

Summary of data sharing alternatives

None of these approaches provide a general purpose data sharing solution capable of modeling data accurately while bridging company and cloud divides and scaling to enterprise-grade levels of throughput. Figure 5 summarizes their respective pros and cons.

Check out part 2 for how modern APIs can solve these legacy issues. Read APIs for Real-Time Data-Sharing